Last week I attended the 18th Biennial Child Vision Research Society meeting at UCL Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health. The meeting included a symposium in honour of the late Oliver Braddick, co-founder of the UCL/Oxford Visual Development Unit together with Janette Atkinson who gave an impressive overview of the unit’s pioneering work on infant vision over the decades as part of the session.

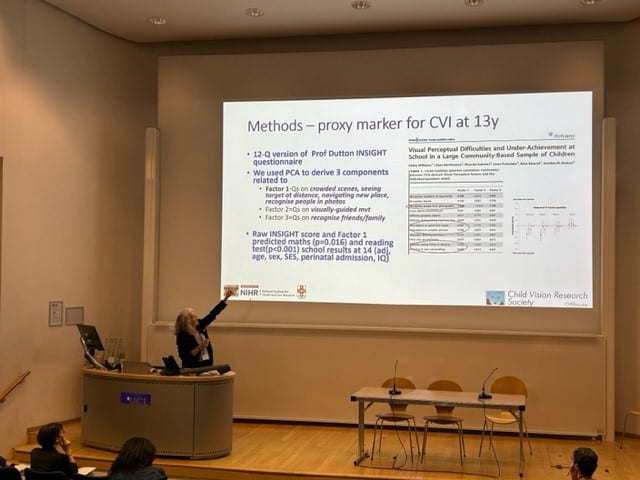

Amongst the many other highlights of the meeting, Cathy Williams (University of Bristol), presented evidence for sub-types of Cerebral Visual Impairment (CVI) in children. It has become apparent recently that a surprisingly high proportion of children in main stream classrooms may have such brain based visual problems.

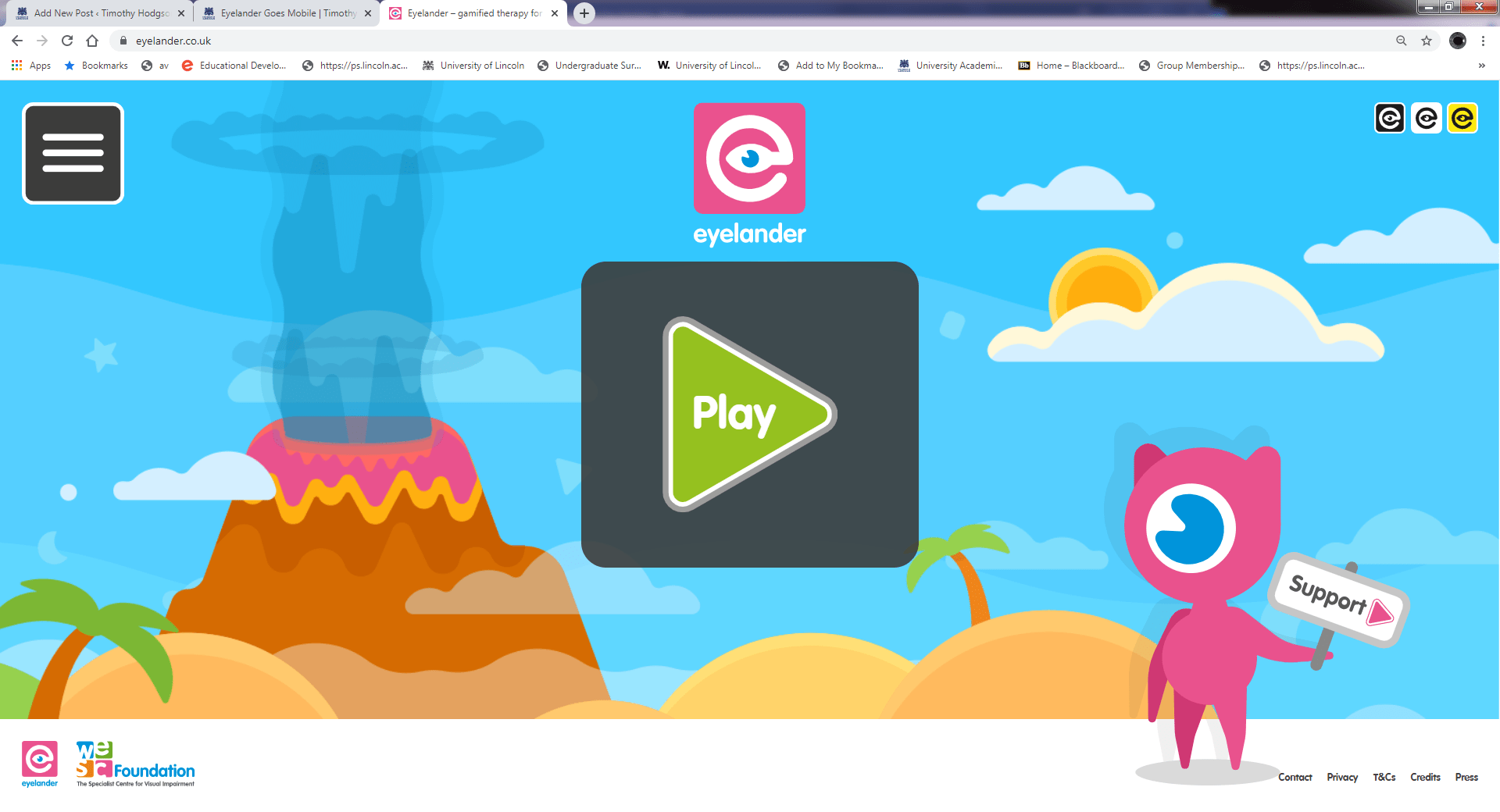

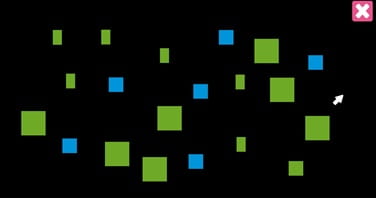

My own talk about the Eyelander game was the last presentation of the conference! But everyone stayed right to the end and seemed to really enjoy it! Eyelander is a gamified version of compensatory visual search training for children with loss of vision on one side (hemianopia) . Selective loss of vision to the left or right might occur following brain injury or neurosurgery, but may also be found in many children with CVI (see above).

I really enjoyed the CVRS meeting. It was great to meet so many new people. In fact, it was one of the friendliest and most enjoyable meetings I’ve ever been to, so I will be sure to go again in 2 years time!