This month we published a paper in the journal Experimental Brain Research reporting how eye movements are influenced by social cues in people with Parkinsons disease.

Previous studies have suggested that Parkinsons patients have problems in directing visual attention due to loss of the chemical dopamine within the basal ganglia of the brain, but no one has specifically looked at whether they have particular problems with social cues. This question is important as problems with processing social information may lead to difficulties in everyday life for people with Parkinsons. It is also a question of scientific interest as it has been suggested that we have specialised brain pathways for processing social information (the so-called “Social Brain hypothesis”).

Previous studies have suggested that Parkinsons patients have problems in directing visual attention due to loss of the chemical dopamine within the basal ganglia of the brain, but no one has specifically looked at whether they have particular problems with social cues. This question is important as problems with processing social information may lead to difficulties in everyday life for people with Parkinsons. It is also a question of scientific interest as it has been suggested that we have specialised brain pathways for processing social information (the so-called “Social Brain hypothesis”).

We used a task in which pictures of someone else’s eyes, arrows and pointing fingers are shown on a computer screen, whilst people track a spot jumping around the screen with their eyes (see picture; you can see a video of the task here). Often people make an eye movement by mistake in the direction indicted by the eyes, arrows or fingers, even when they are meant to respond directly at the target (the little black spot) and ignore the pictures. We found healthy adults made more of these errors with pointing finger cues compared to the other cue types (suggesting pointing fingers provide a particularly strong cues to eye movements) whereas people with Parkinsons made similarly high errors for all 3 cue types.

Although not specifically better or worse for socially relevant cues (eyes / fingers), Parkinsons patients clearly had difficulty in suppressing their distracting influence. This suggests the basal ganglia plays a role in controlling eye movements in response to social and non-social cues. But this doesn’t mean that people with Parkinsons don’t have particular problems with maintaining attention in social situations. On the contrary, social  interaction might often take place in a busy environment, with lots of sensory information competing for attention. These deficits in the control of eye movements might therefore lead to difficulty in social interaction and might impact on patients’ quality of life.

interaction might often take place in a busy environment, with lots of sensory information competing for attention. These deficits in the control of eye movements might therefore lead to difficulty in social interaction and might impact on patients’ quality of life.

A link to the paper can be found here

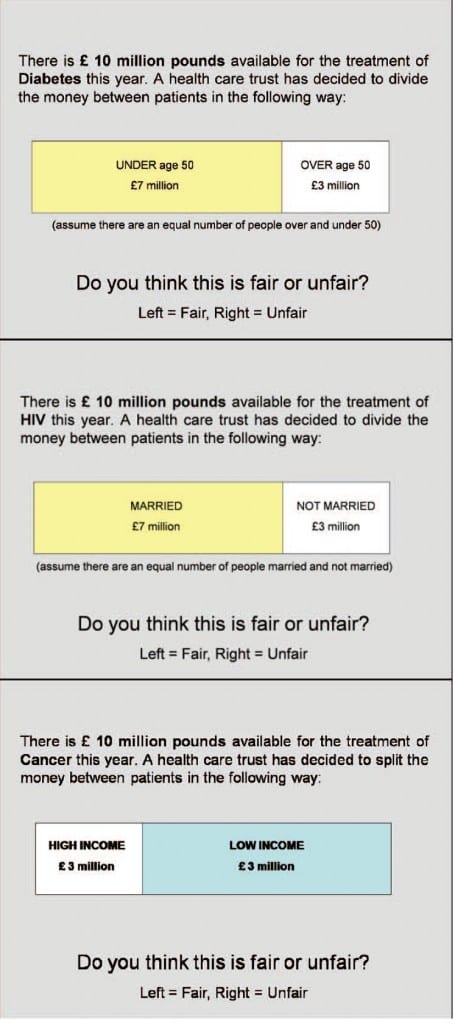

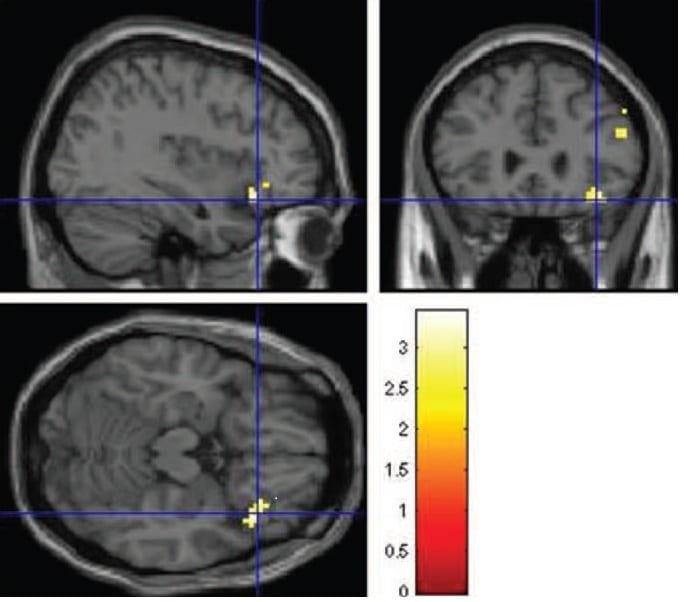

n the June edition of the Journal of Neuroscience Psychology and Economics. The research was carried out in collaboration with Prof. Paul Anand ( Open University and Health Economics Research Centre at the University of Oxford), Lisa Smith (Flinders University Austrailia) and the Exeter Magnetic Resonance Research Centre. A pre-print of the paper is available via the Lincoln Repository

n the June edition of the Journal of Neuroscience Psychology and Economics. The research was carried out in collaboration with Prof. Paul Anand ( Open University and Health Economics Research Centre at the University of Oxford), Lisa Smith (Flinders University Austrailia) and the Exeter Magnetic Resonance Research Centre. A pre-print of the paper is available via the Lincoln Repository